Aftermath

Five Widows & An International Media Sensation

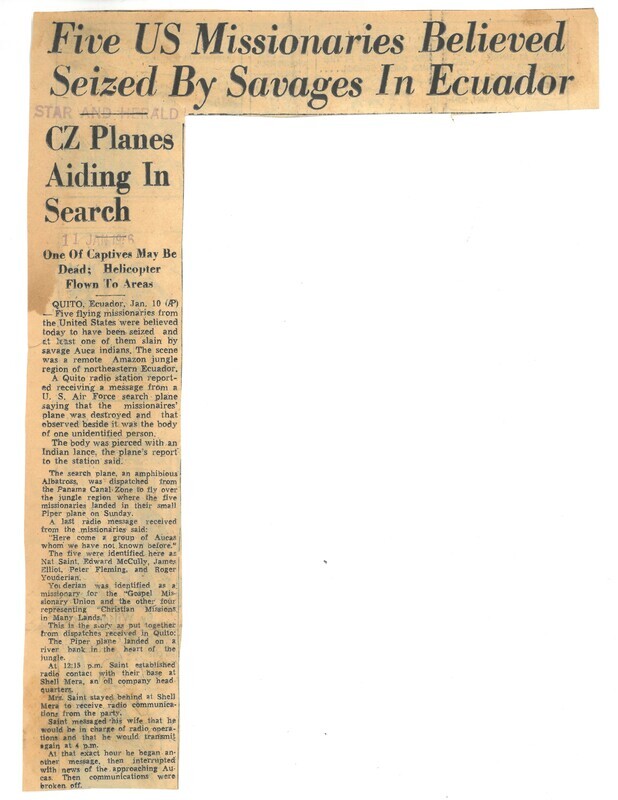

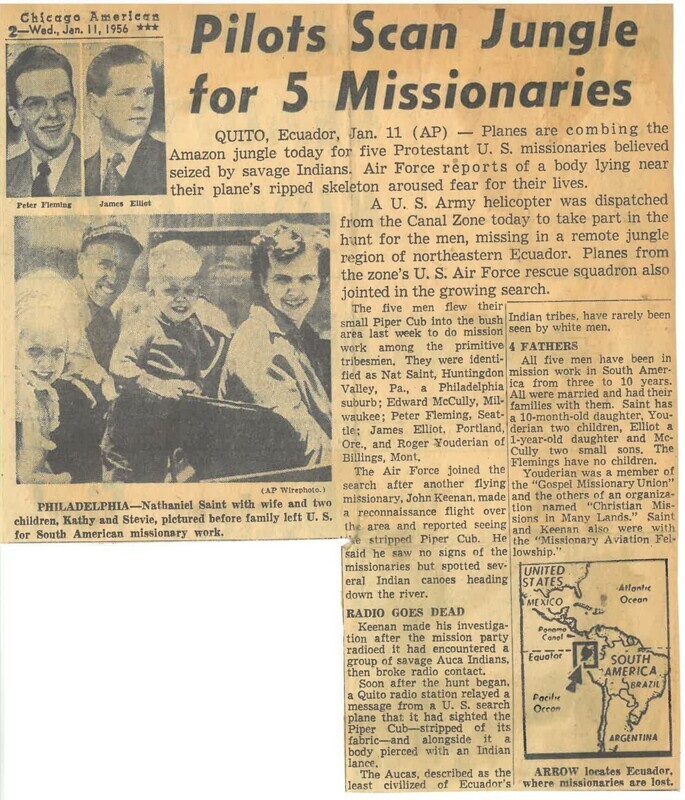

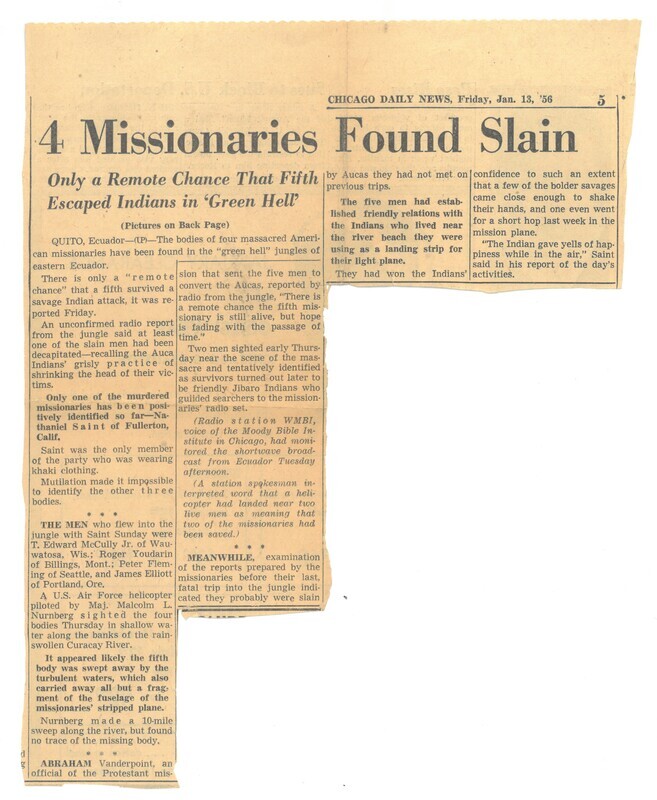

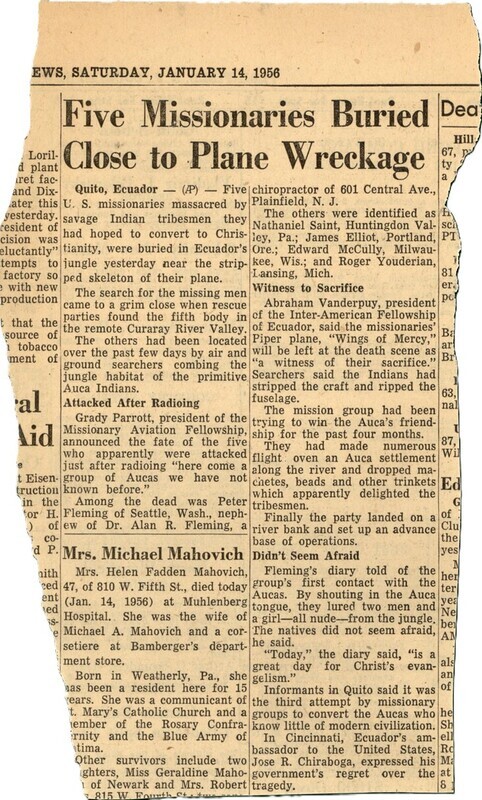

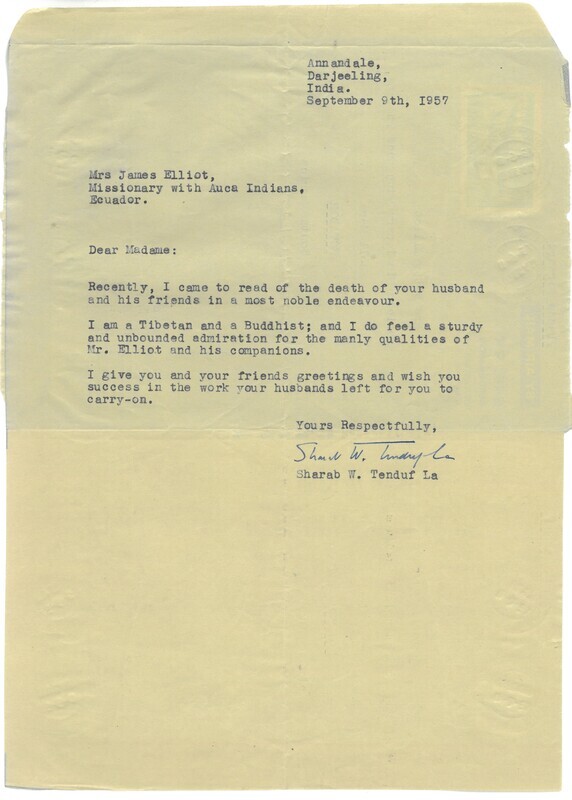

The tragic events in the Ecuadorian rainforests in January 1956 evolved into a news media sensation in the months and years following the death of the five missionaries. As more details emerged, the American public, both evangelical and secular, was gripped by the dramatic story of young idealistic missionaries murdered while using modern technology to contact an isolated people group with the Christian message of love and forgiveness. Newspaper headlines followed the search parties down river and into the jungle, while mainstream magazines featured stark black and white photos of the grieving widows and their nine now-fatherless children. Journalists rushed to interview relatives, former classmates, and friends of the five men, eager to describe the faith and convictions that led them to their deaths on Palm Beach. The story of “Operation Auca” quickly acquired iconic status among American Evangelicals, especially after Elisabeth Elliot, her daughter Valerie, and Rachel Saint reentered the rainforest to live among the Waorani two years later.

Over the next several years, the tragedy on Palm Beach evolved from a riveting tale of violence, grief, and inspirational faith into a wider narrative of sacrificial love, forgiveness, and redemption. The story of Jim Elliot and his missionary friends was spread and sustained through repeated retellings in books, articles, radio and television programs, films, and, in later decades, digital media, embedding the narrative deeply within evangelical missionary mythology and enshrining Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Peter Fleming, Ed McCully, and Roger Youderian as missionary martyrs. In the second half of the twentieth century, many evangelical missionaries credit their own entry into Christian service to the spiritual example of the five men.

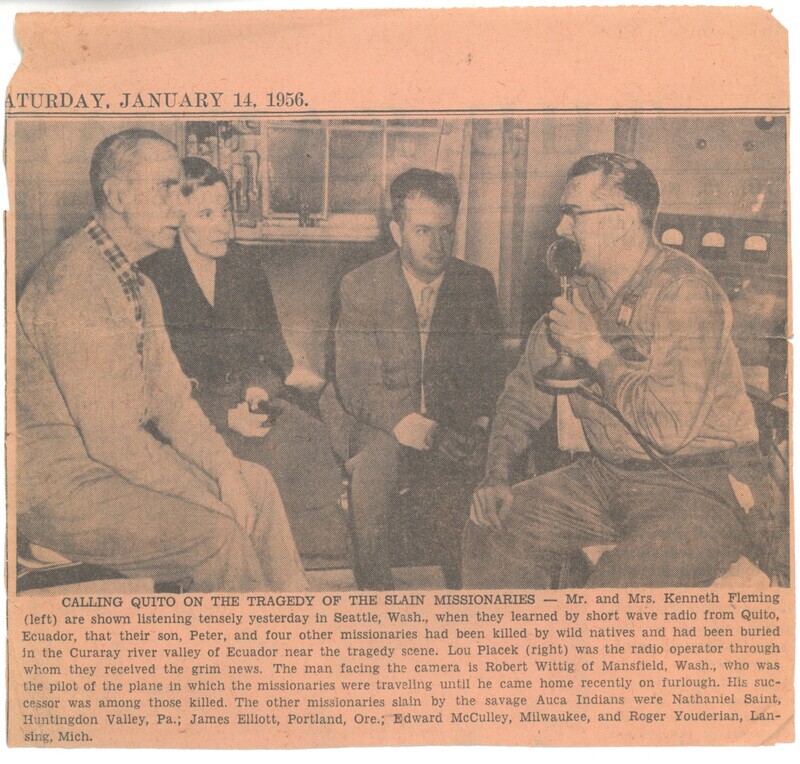

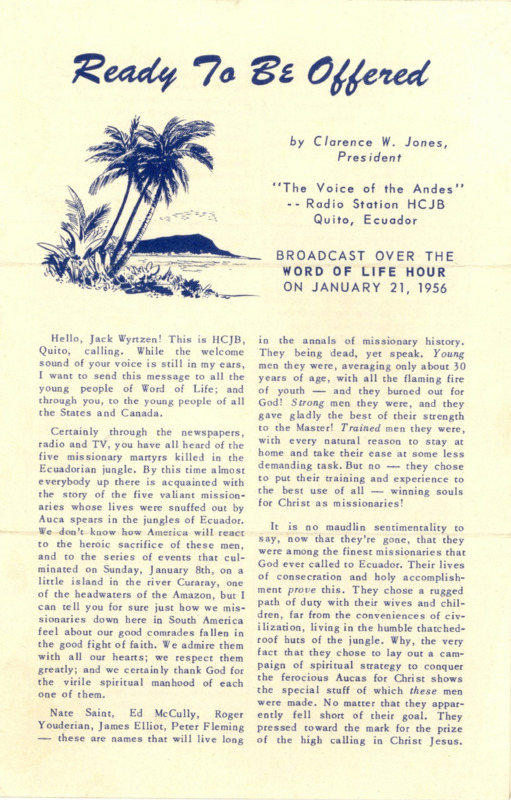

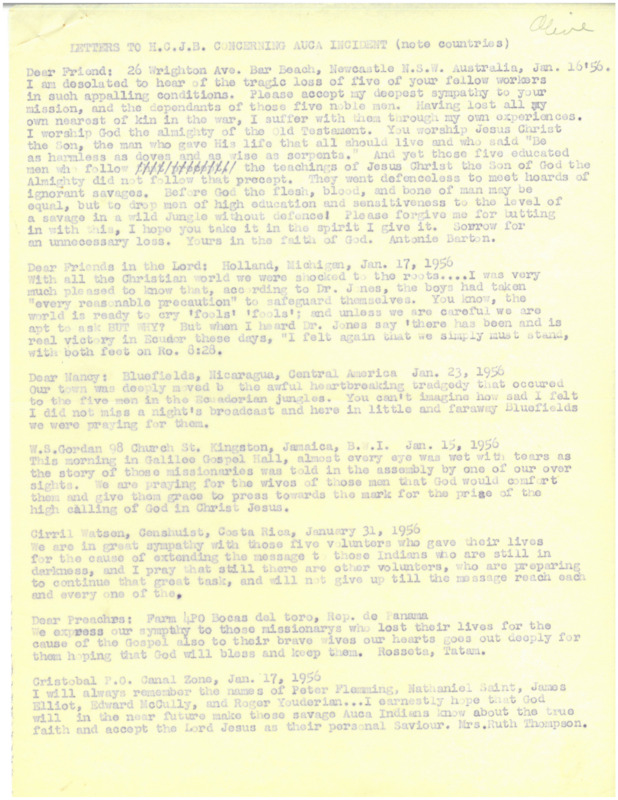

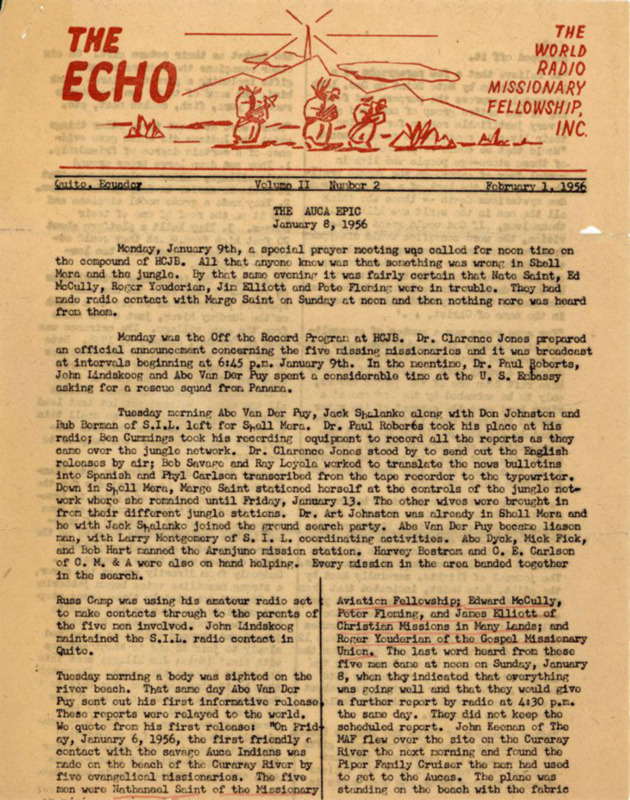

Radio

Across the Ecuadorian Amazon, radio provided one of the few consistent points of contact between remote mission station superintendents and missionaries. While on Palm Beach, Nate Saint maintained regular radio check-ins with his wife Marjorie at the base in Shell Mera. When Nate missed one of these scheduled communications, it was first signal that something had gone wrong. Continued radio silence prompted fellow missionaries to alert authorities, drawing in the U.S. Army and Ecuadorian military to assist with search and rescue operations. On January 9, the missionary radio station HCJB broadcast a report on the missing Americans from Quito to a global audience. After the men’s bodies were recovered and buried, HCJB devoted its January 15 episode of the popular Back Home Hour program to a memorial service for the missionaries. Accessible via shortwave radio all over the world, the broadcast generated hundreds of letters, cables, and telephone calls in response.

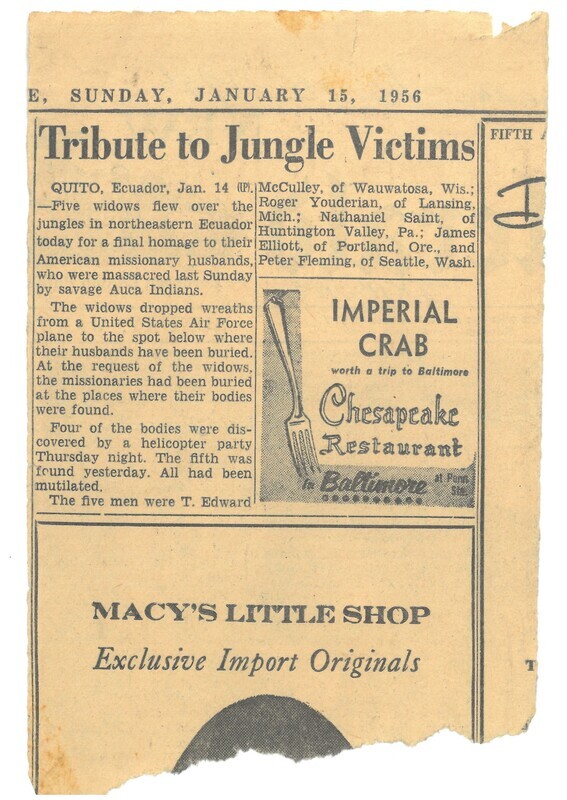

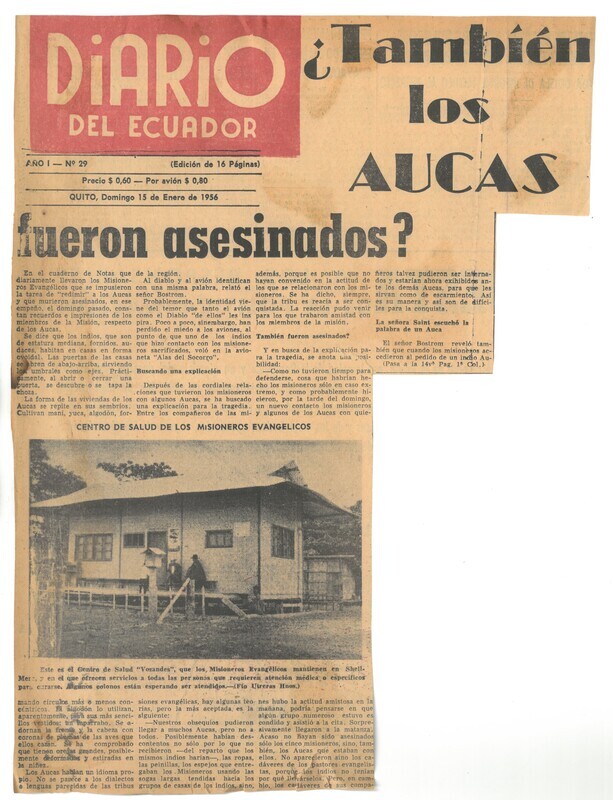

Newspapers & Magazines

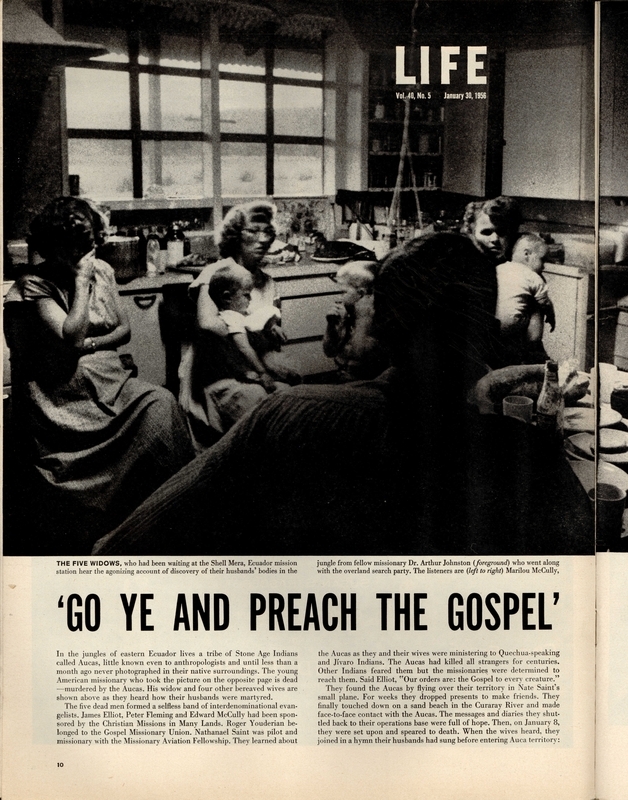

The sudden, shocking deaths of the five young American missionaries quickly became a major story in both secular and religious media following the initial reports of their disappearance and then the confirmation of their deaths. Coverage appeared in newspapers across the United States, particularly in the hometowns of the fallen missionaries, but also major U.S. magazines, such as Life and Time. Follow-up articles appeared for years afterwards, particularly in Life magazine. Photographer Cornell Capa contributed influential photo essays to Life, first documenting the aftermath of the killings and later portraying the mission of Rachel Saint and Elisabeth Elliot, as they lived among the Waorani.

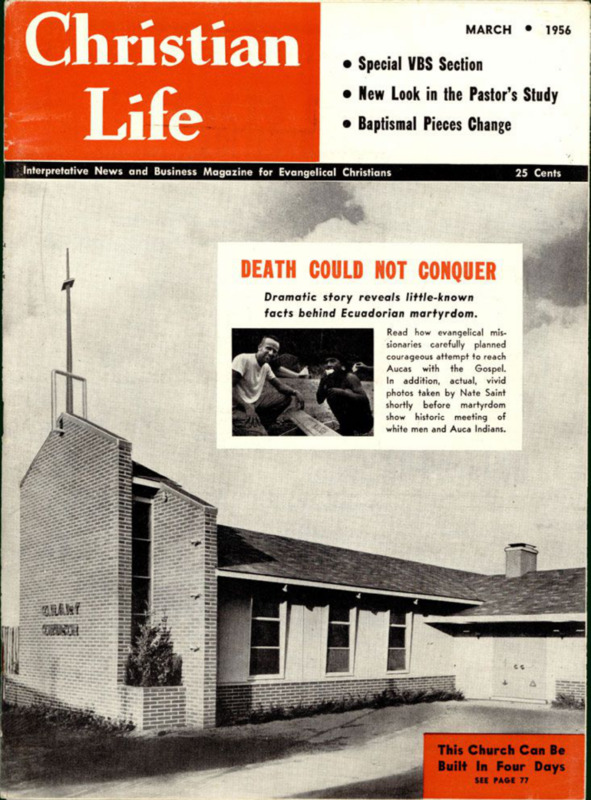

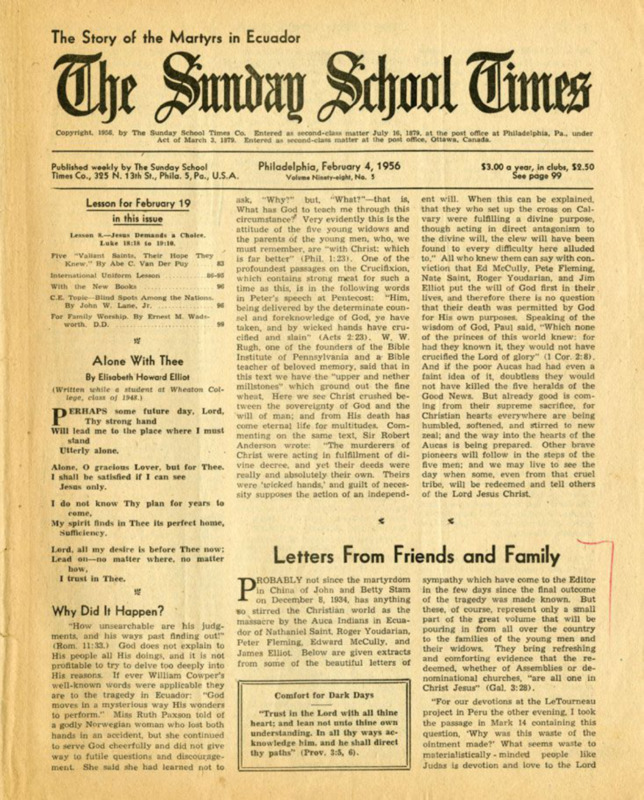

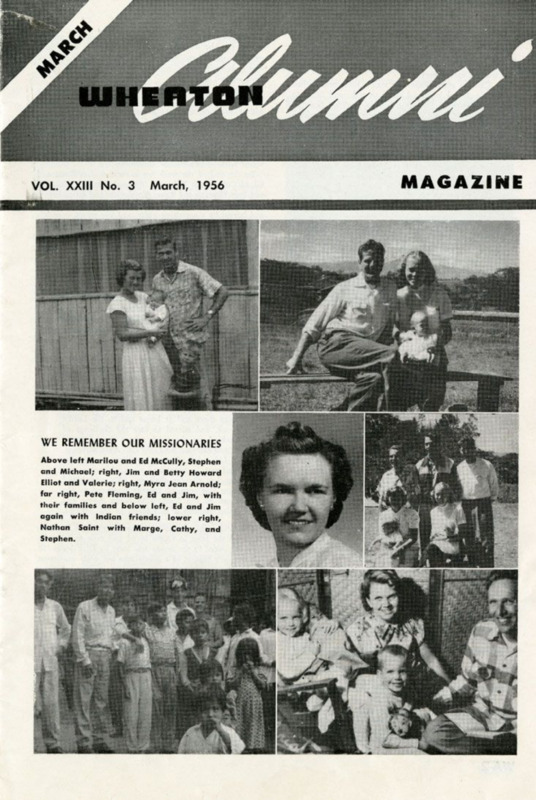

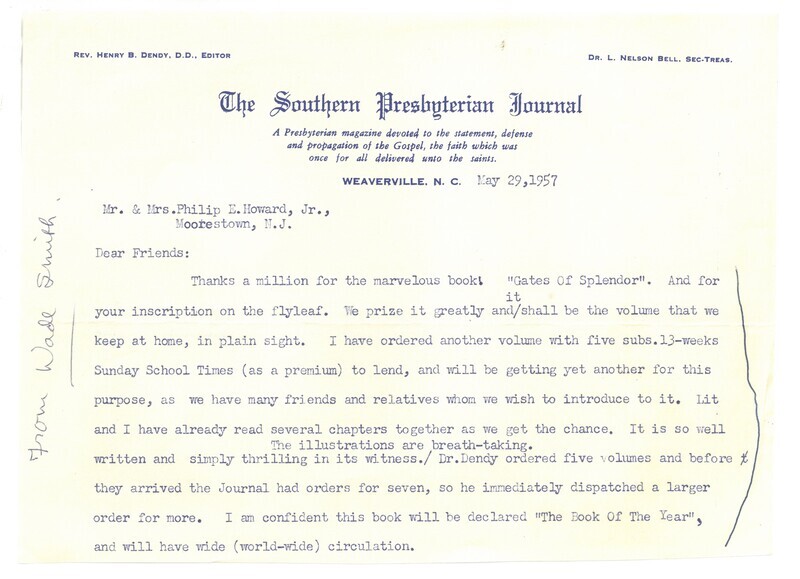

Evangelical and fundamentalist Christian magazines also covered the events in Ecuador extensively, often drawing on personal or institutional ties to the missionaries. Publications like the Sunday School Times (formerly edited by Elisabeth Elliot’s father), Moody Monthly, or the Wheaton College Alumni Magazine (the alma mater of the Elliots, Ed McCully, and Nate Saint) featured articles that often identified the five men as “missionary martyrs,” framing the story within the larger context of evangelical identity and missions history.

Literature

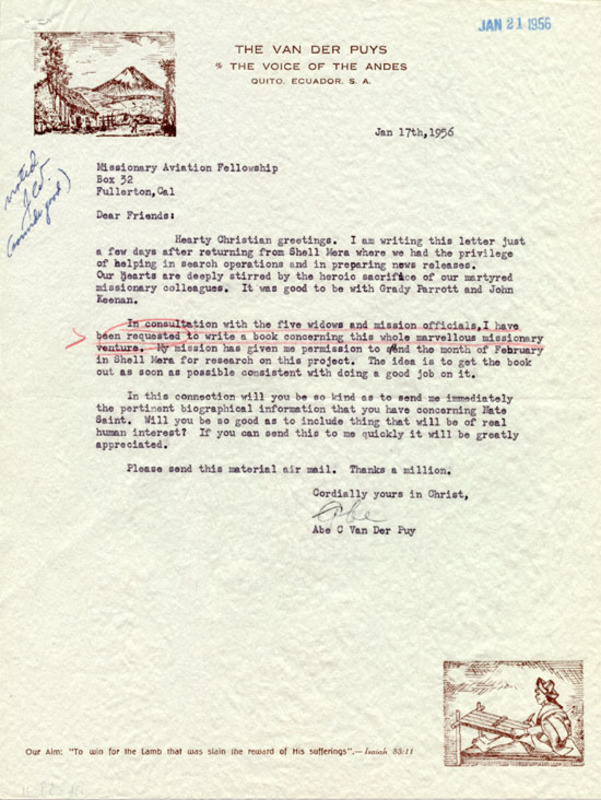

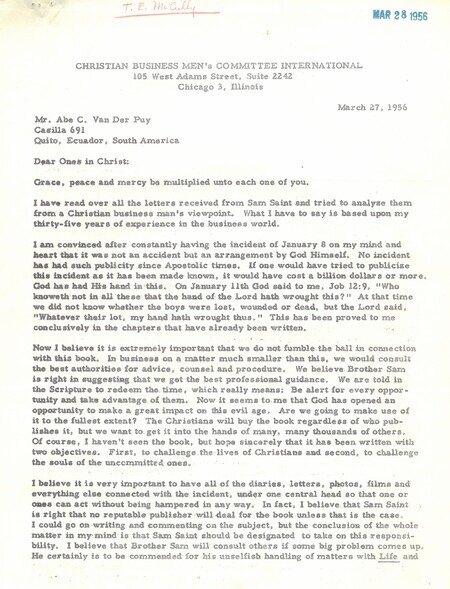

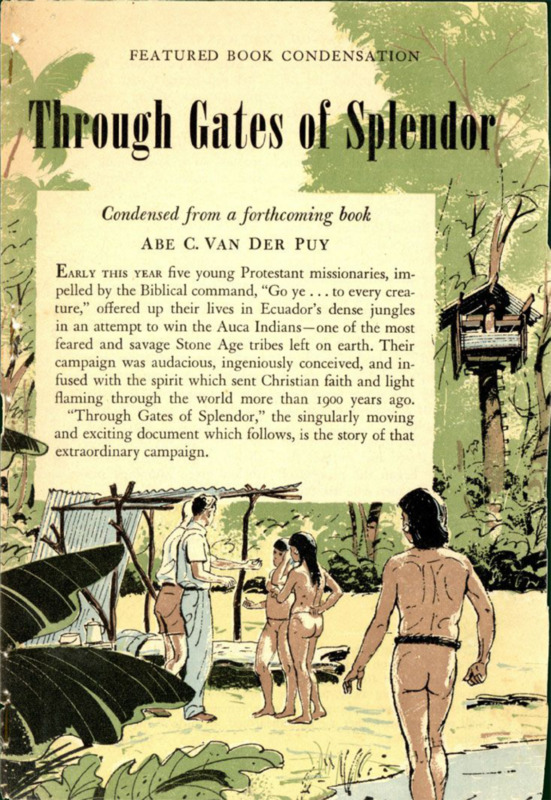

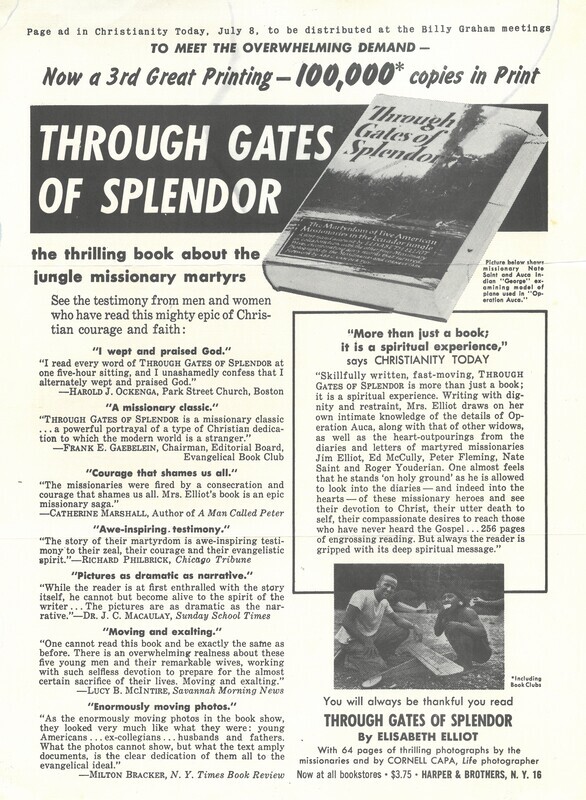

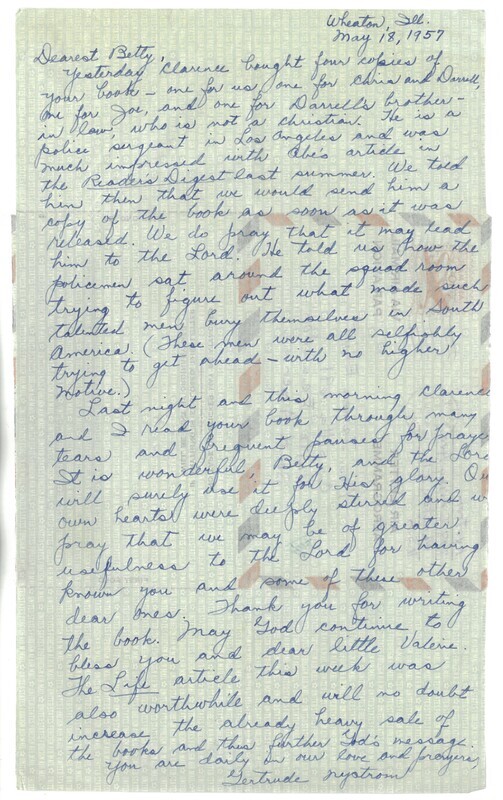

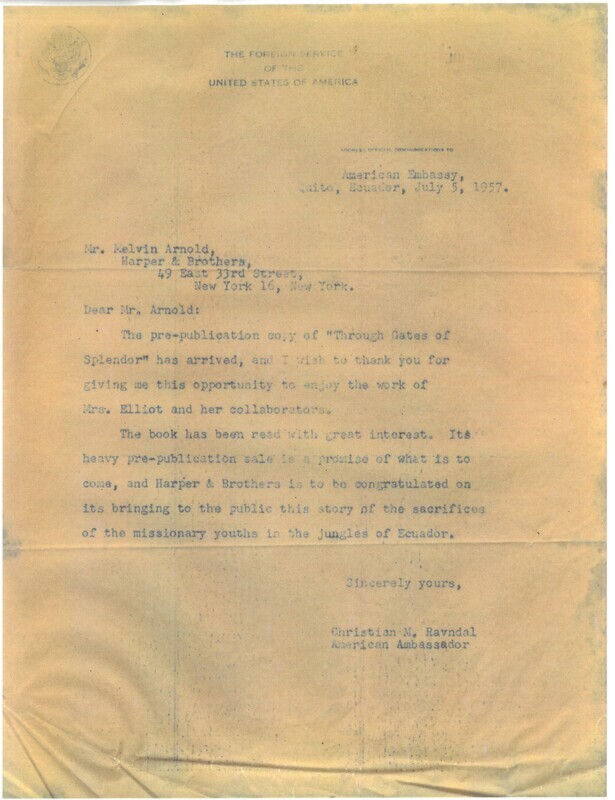

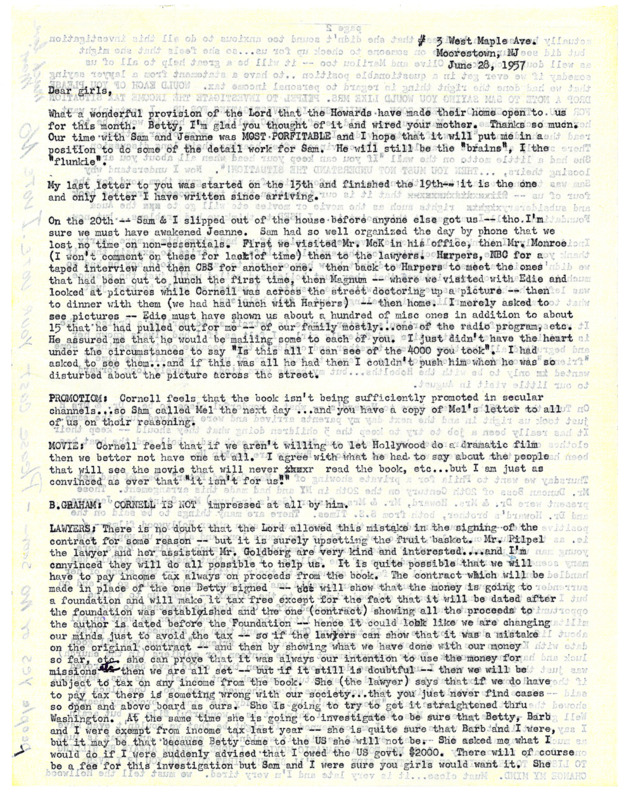

Plans for a book documenting “Operation Auca” began within a week of the men’s deaths. The five widows initially asked Abraham Van der Puy, Ecuador field director for HCJB, to write the story. Van der Puy compiled extensive notes that served as the basis for a condensed Reader’s Digest version completed by editor Clarence Hall in August 1956, but other duties soon took him away from the book project. After meeting with Harper & Brothers in the fall of 1956, Elisabeth Elliot assumed authorship, and Through Gates of Splendor was published in May 1957. An immediate bestseller, the book powerfully shaped popular evangelical memory surrounding “Operation Auca,” cementing Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Ed McCully, Peter Fleming, and Roger Youderian as legendary figures in mid-twentieth-century American missions.

In the decade that followed, the success of Through Gates of Splendor led to several related book projects from Elisabeth Elliot: The Shadow of the Almighty (1958), The Savage My Kinsman (1959), and an edited collection of her husband’s journals. Although Elliot was the most prolific and well-known chronicler of the missionary work with the Waorani, other publications also emerged. Russell Hitt’s Jungle Pilot (1959) offered a biography of Nate Saint, and Ethel Emily Wallis’s The Dayuma Story: Life Under Auca Spears (1960) presented an account of Dayuma’s early life and conversion. In 1998, Olive Fleming Liefeld also published her own account focused on Pete Fleming in Unfolding Destinies: The Ongoing Story of the Auca Mission.

Film

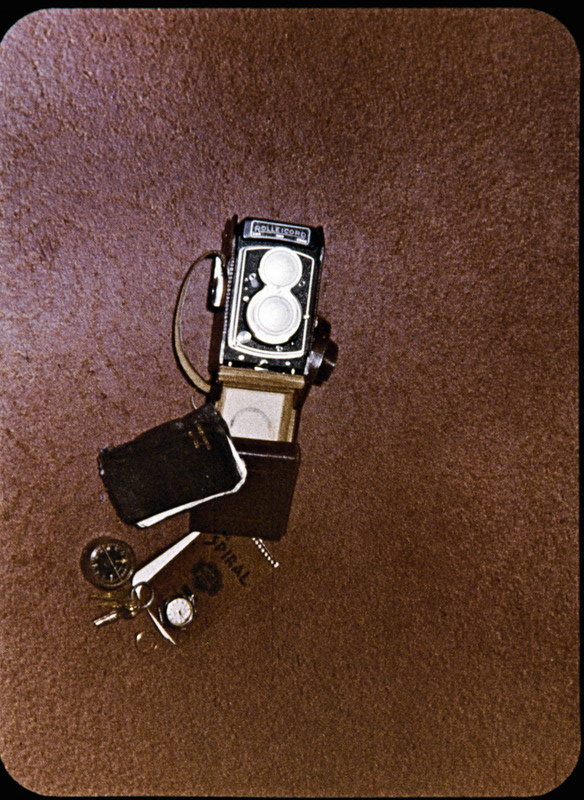

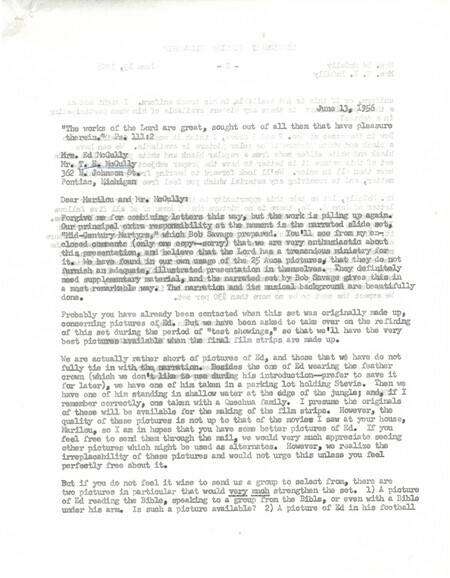

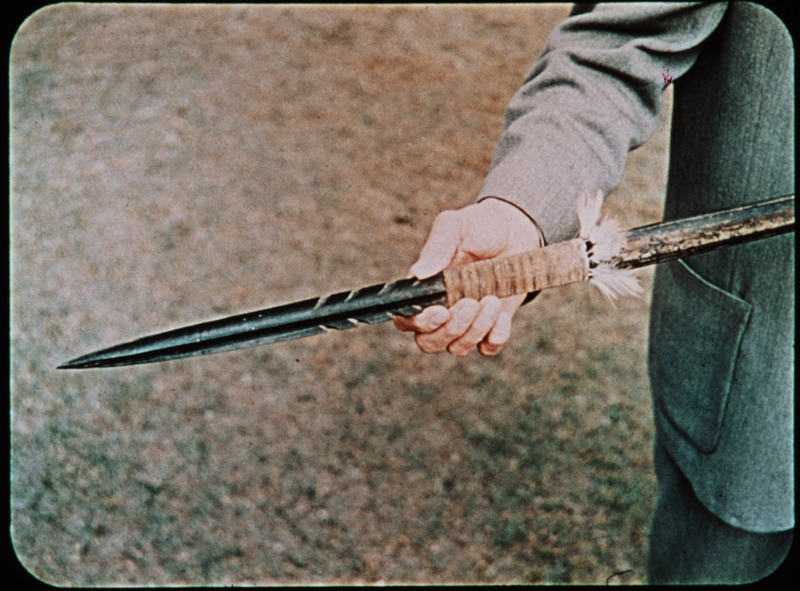

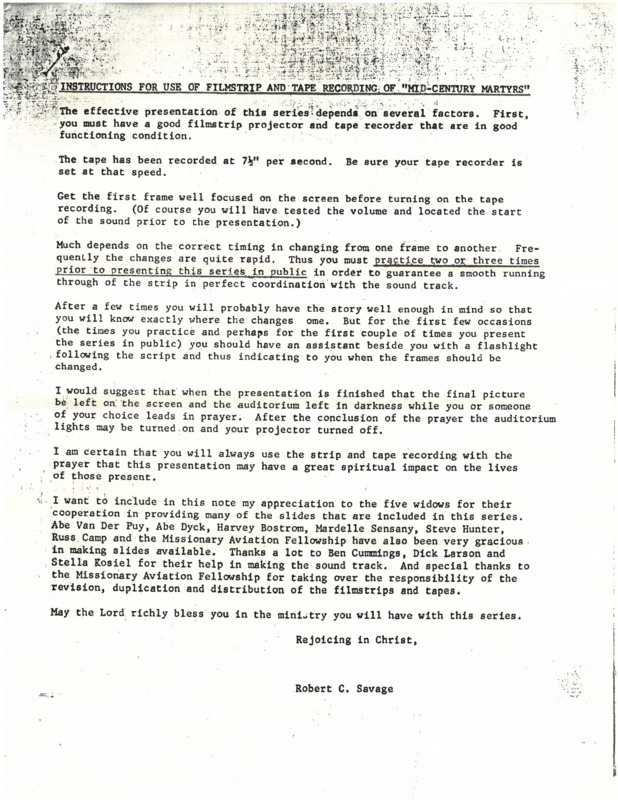

From the emotionally charged photographs of the five new widows taken by Cornell Capa to the negatives recovered from Nate Saint’s discarded camera, visual media played a central role in the American public’s connection to the tragedy. Recognizing the power of images to communicate the story of the five missionaries and the Waorani, Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) and HCJB, with the cooperation of the five widows, developed a filmstrip in the early summer of 1956. Titled Mid-Century Martyrs, the filmstrip offered biographies for the five missionaries, background on the Waorani, and an account of the “Operation Auca” planning and aftermath. Initially used only by the mission organizations associated with the five missionaries, the global reach of the story soon led to requests for the filmstrip from other Christian missionaries, organizations, and churches. Although concerned about further sensationalizing the men’s deaths, MAF and the five widows also saw the value of the filmstrip for raising awareness and funds for missions in Ecuador. In late 1956, MAF also created a second filmstrip, Unforgettable Friday, that centered on the life and work of Nate Saint.

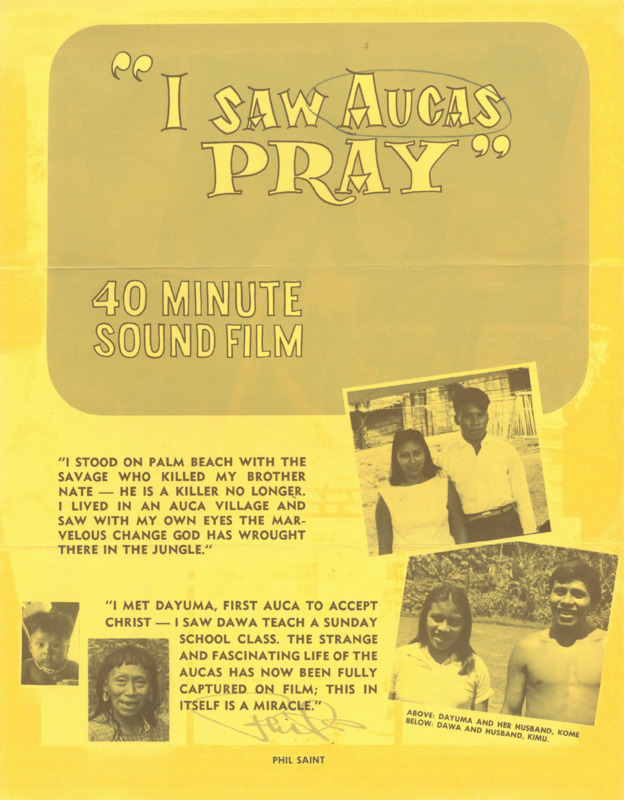

Following the success of Elisabeth Elliot’s book Through Gates of Splendor, the use of visual storytelling expanded to film. In 1961, the Auca Missionary Foundation (established to represent the five widows) partnered with Sacred Cinema to produce a film adaption of the book, illustrated with home movies made by Nate Saint and Elisabeth Elliot and photographs from Cornell Capa. Like many Christian films of the mid-century, the film was distributed through individual rentals to churches, youth groups, and mission organizations. Several other films followed over the decades, including I Saw Aucas Pray (1963), Beyond Gates of Splendor (2002), and End of the Spear (2005).

![click to see item Letter from Goro Nakano, Japanese journalist and historian, to Elisabeth Elliot regarding the Japanese edition of <i>Through Gates of Splendor</i>, January 1958. Nakano writes that while the book was published under Harper & Brothers' religious department, he "believe[s] it should be published in Japan not only as a religious book but as a great adventure book and sublime human document." In the years after its English release in 1957, <i>Through Gates of Splendor</i> was translated into many languages, including German, Portuguese, Russian, Turkish, Spanish, and Japanese.](/to-carry-the-light-further/objects/small/2780918_19580110_sm.jpg)

![click to see item Letter from Marjorie Saint to "Dearest four, and Sam [Saint]", August 1957. The two page letter primarily concerns the ongoing question of the proposed documentary film on "Operation Auca," including Marj's meetings with Gospel Films and comments on Ken Anderson of Ken Anderson Films, Dick Ross of World Wide Pictures, and the distribution prospects for Christian films.](/to-carry-the-light-further/objects/thumbs/7010207_saint1a_th.jpg)