Pioneer Territory

People, Places, and Early Preparation

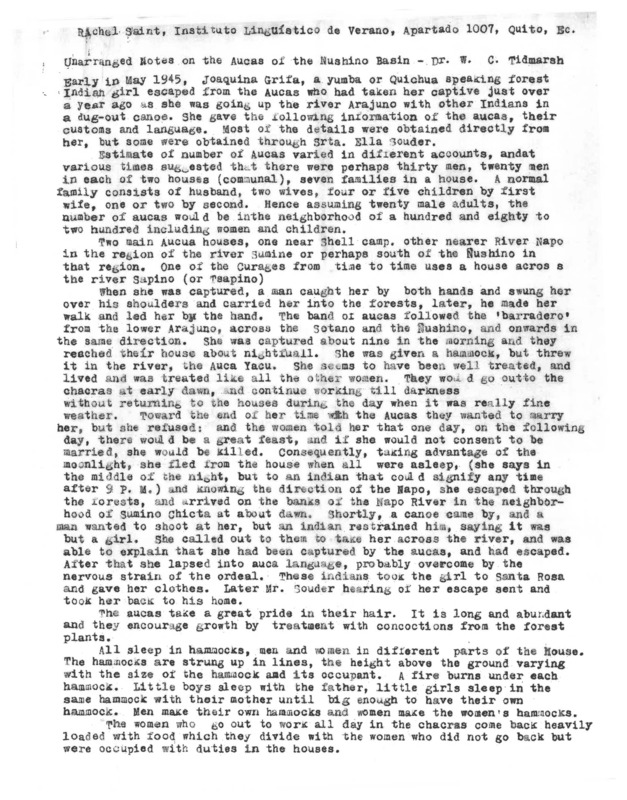

In the late 1940s, Dr. Wilfred Tidmarsh, a British missionary working with the Plymouth Brethren’s Christian Missions in Many Lands in eastern Ecuador, began to hear stories about the Waorani, an isolated indigenous people group. The neighboring Quichua people called the Waorani “Aucas,” a derogatory term meaning “savages,” and lived in fear of Waorani attacks and revenge killings.

Numbering between 500 and 1,000 members in the mid-twentieth century, the Waorani lived in small, nomadic kin-based communities between the Napo and Curaray Rivers of eastern Ecuador, an area of roughly 8,000 square miles. Although divided into four regional sub-groups, the Waorani were united by a common language, Wao Tededo, a language isolate with no writing system. Waorani society was highly egalitarian and individualistic, with no chiefs or cultural stratification and community activities often limited to immediate kin groups. Within kinship groups, however, the Waorani generally divided labor by gender—men hunted monkeys, toucans, marmosets, and deer with blowguns or spears, while women cultivated gardens of manioc and plantains. These family settlements raided each other frequently, both within and across the sub-groups, seeking new marriages or avenging previous attacks. Genealogies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s concluded that in the previous five generations this intergroup violence accounted for around 40 percent of all adult deaths, with another 20 percent resulting from external raids. Having survived the incursion of corporate rubber and oil prospectors into the Ecuadorian rainforests, the Waorani fiercely resisted external contact with neighboring indigenous groups, the Ecuadorian government, or growing numbers of Western missionaries, archaeologists, and anthropologists.

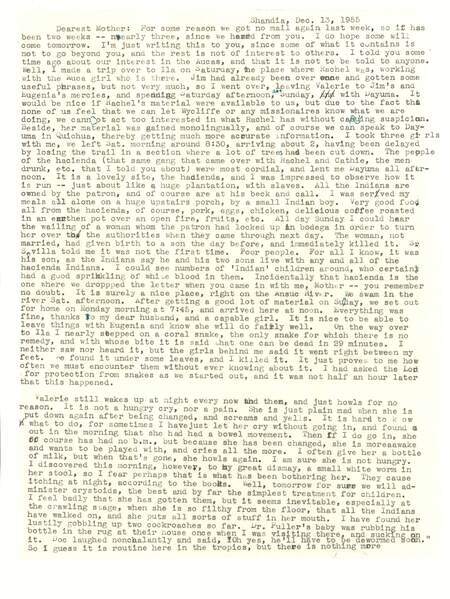

Despite the Waorani’s reputation for violence towards outsiders, Wilfred Tidmarsh became fascinated with the idea of bringing the Christian gospel to this unreached indigenous people group. With no avenue for direct contact, Tidmarsh began making lists of Wao vocabulary words he learned through his work with the Quichua at the Shandia mission station.

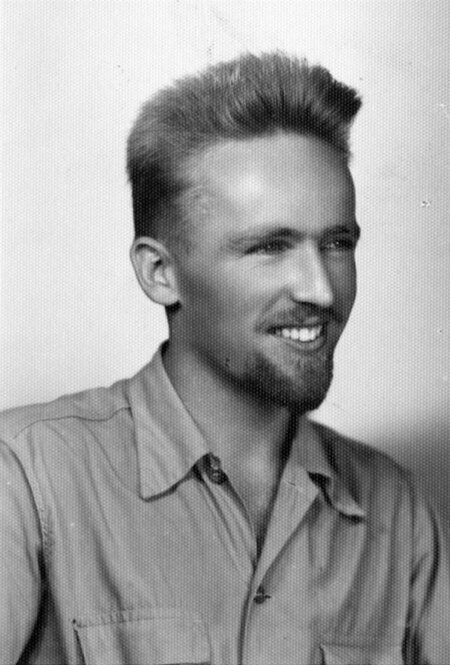

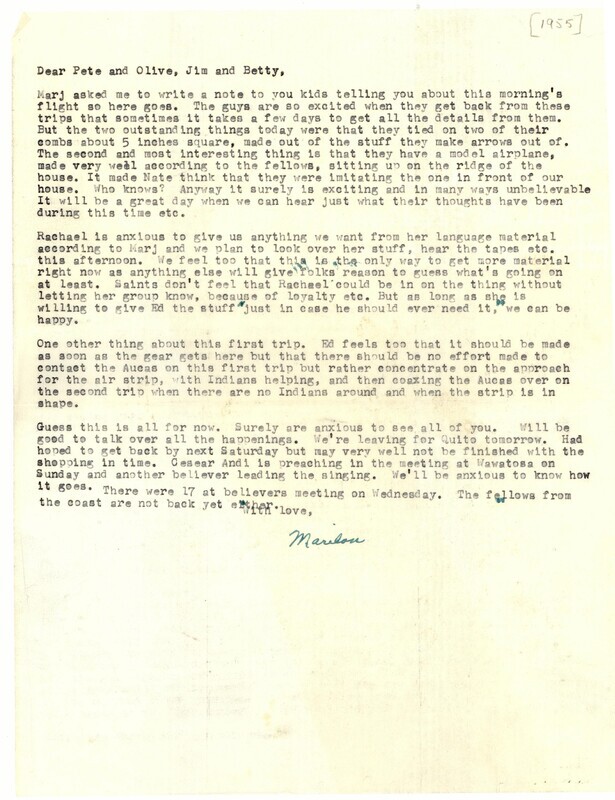

In October 1949, recent Wheaton College graduate and aspiring missionary Jim Elliot learned about Dr. Tidmarsh from his brother, Bert Elliot, a new missionary to Peru. Inspired by Tidmarsh’s work with the Quichua, Elliot began seriously considering mission work in Ecuador. On a furlough trip to the Pacific Northwest in July 1951, Tidmarsh met Elliot and his friend, Peter Fleming, sharing his hopes to reach the Waorani. Inspired by the veteran missionary’s vision, the two young Portland, Oregon natives determined to join the work in Ecuador. When Peter Fleming wrote to Tidmarsh, now back in Ecuador, describing their desire to join him at Shandia, Tidmarsh agreed. The first of several American missionaries en route to South America, Fleming and Elliot sailed for Ecuador in February 1952, later joined by Elisabeth “Betty” Howard and Ed and Marilou McCully.

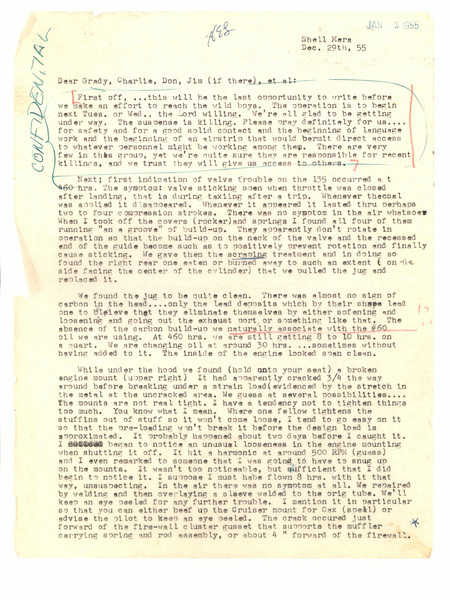

While developing the mission station at Shandia, Jim Elliot, Ed McCully, and Peter Fleming met Nate Saint, a pilot with Mission Aviation Fellowship. Based in Shell Mera, Nate flew missionaries and supplies to remote mission outposts scattered throughout the dense rainforests of eastern Ecuador. Through their work together, the four men discovered a mutual interest in reaching the Waorani with the gospel.

Plans to contact the Waorani began in earnest in September 1955, after Saint and McCully spotted a clearing with a Waorani village from the air. The men called this cluster of homes “Terminal City.” A few years earlier, Saint had developed an innovative method for communicating with people on the ground from the air. The procedure required the pilot to lower a telephone in a bucket from a small plane to the ground. If the pilot flew in a slow circular pattern, it was possible for someone on the ground to hold the telephone and communicate with the pilot. With practice, Saint refined this method to become what he called “the bucket drop.”

In October, Nate Saint, sometimes accompanied by Ed McCully, Pete Fleming, or Jim Elliot, began contacting the Waorani in Terminal City via bucket drops with small gifts. Sometimes, the Waorani sent gifts back up in the bucket, including a parrot. The missionaries also began using a loudspeaker from the plane to broadcast brief friendly messages in broken Wao. Throughout the fall of 1955, the missionaries made 12 flights over the Waorani clearing.

Supplementing Tidmarsh’s rudimentary Wao vocabulary, the men also learned a smattering of words and phrases from Dayuma, a Waorani woman who fled her village eleven years earlier after her father was speared to death. As they later learned, none of the missionaries knew that Dayuma had forgotten or repressed much of her knowledge of Wao Tededo, after not speaking the language for more than a decade. The phrases the men shouted from Saint’s plane were a broken form of the language and unintelligible to the Waorani.

Not all the missionaries were as confident as Jim Elliot or Nate Saint about the plans for contacting the Waorani. A newlywed, Peter Fleming, had only recently returned with his wife Olive at their jungle mission station before he began expressing doubts. Fleming questioned God’s calling to participate in the Waorani project if it risked the lives of the missionaries and jeopardized the crucial work with the Quichua at the Shandia mission station. While Fleming wrestled with his decision to join the mission, Elliot and McCully looked for a possible fourth man to join the first contact party. At Nate Saint’s recommendation they recruited Roger Youderian, an experienced pioneer missionary to the Shuar people in Ecuador. In the end, Peter Fleming overcame his doubts and both Fleming and Youderian agreed to participate.

By the end of December 1955, the five American missionaries decided to take the next step of faith in their efforts to contact and evangelize the Waorani. Encouraged by their gift exchanges and seemingly friendly response from the Waorani over the last four months, the missionaries decided to move forward in the new year with the next phase of “Operation Auca” — direct, face-to-face contact.