New Marching Orders

Long-Term Impacts & Continuing Work

From the initial radio reports to the iconic Life magazine feature, the five widows faced an enormous wave of publicity after their husbands’ deaths. The early months of 1956 were filled with interviews, speaking engagements, reports, and travel, including trips to the United States for Elisabeth Elliot, Olive Fleming, and Marilou McCully.

Across Ecuador and the United States, efforts to memorialize the five men served a dual purpose—celebrating the missionaries’ sacrificial deaths and finding new resolve amid the widows’ shock and grief. In February, Olive Fleming, Marj Saint, Barbara Youderian, and Abraham Van der Puy attended a ceremony in Quito where Ecuadorian President José María Velasco Ibarra formally honored the sacrifice of the five missionaries and praised the work of HCJB and evangelical missions in Ecuador. At Wheaton College in Illinois, President V. Raymond Edman commissioned the naming of two dormitories and an athletic field in honor of alumni Elliot, Saint, and McCully. Writing to the staff of Mission Aviation Fellowship shortly after the deaths were announced, Edman framed the men’s legacy as a call to continued service:

“[My] heart has been deeply stirred during these days by the word about these three Wheaton boys who have been martyred in eastern Ecuador. They were leaders here on campus and had the possibilities of going to the top of any field of endeavor; but they preferred to give all to the Lord of the harvest so that those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death might see the Light of the world.... Do be trusting with us that many will be hearing the call to carry the Light further into the darkness because of what Nate and the other lads have done for the Lord Jesus.”

For the five women widowed in Ecuador, this call could scarcely be a more immediate or personal question. They had come to Ecuador intent on lifelong missionary service in the remote rainforests where the gospel had never before been preached. Now disoriented by grief and unrelenting media attention, Elisabeth Elliot, Olive Fleming, Marilou McCully, Marj Saint, and Barbara Youderian sought new marching orders.

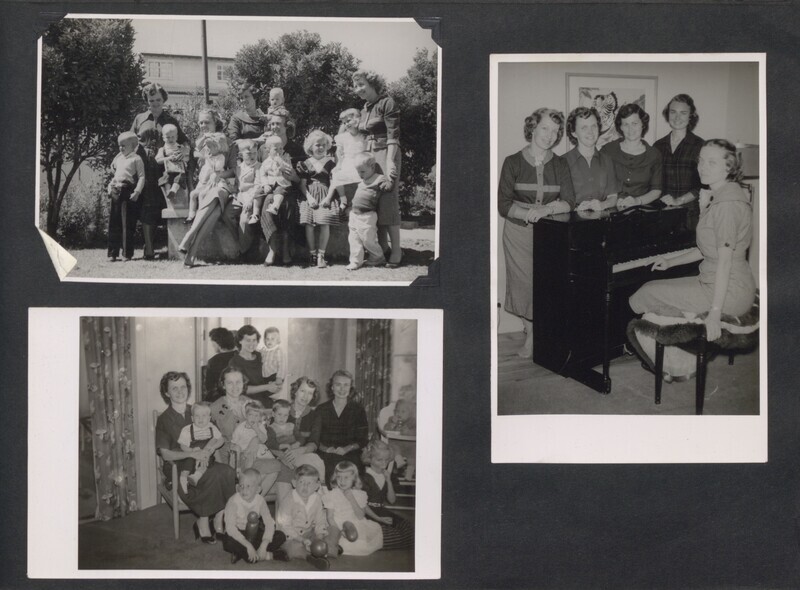

The women met together for the last time in Quito in January 1957 before dispersing to new assignments across Ecuador and the United States. Yet even as their paths diverged, the widows remained central to the public narrative of the “Auca Incident” and to emerging plans to continue the five men’s mission to the Waorani.

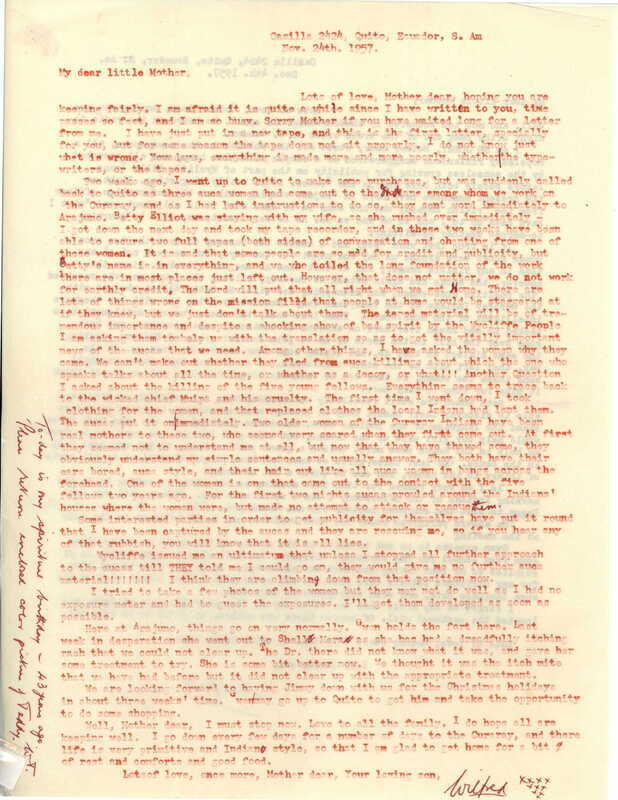

Caught between the competing evangelistic approaches and priorities of independent Brethren missionaries, the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), and Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF), strategies to renew contact with the Waorani developed slowly. MAF pilots Johnny Keenan and Hobey Lowrance continued gift drops over the Waorani settlements. Rachel Saint pursued a parallel project to translate the Wao language with Dayuma. Dr. Wilfred Tidmarsh broadcast friendly messages to Waorani villages from an MAF airplane and built a hut in Waorani territory near a small Quichua settlement. Another Waorani attack on the hut in October 1957 again brought efforts to a standstill.

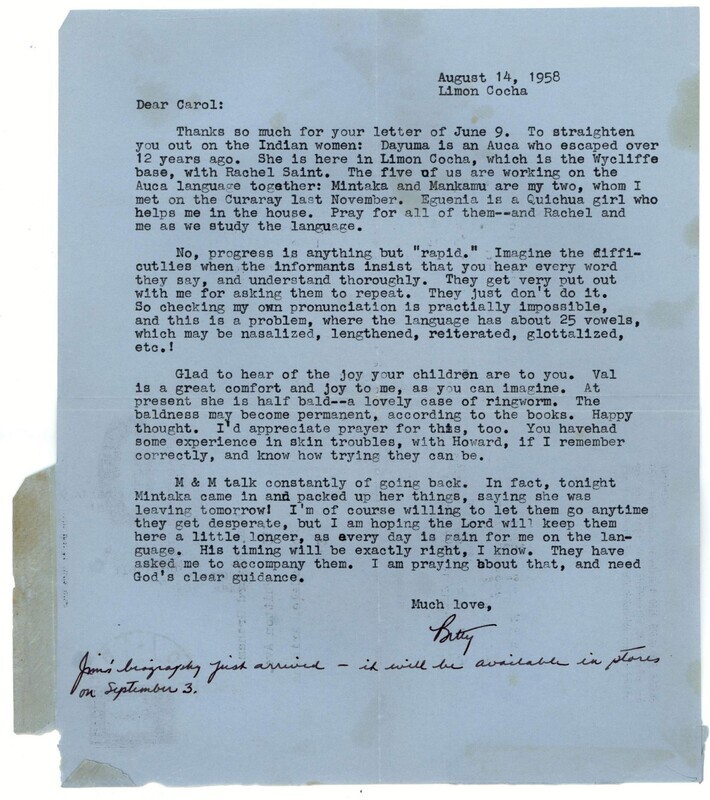

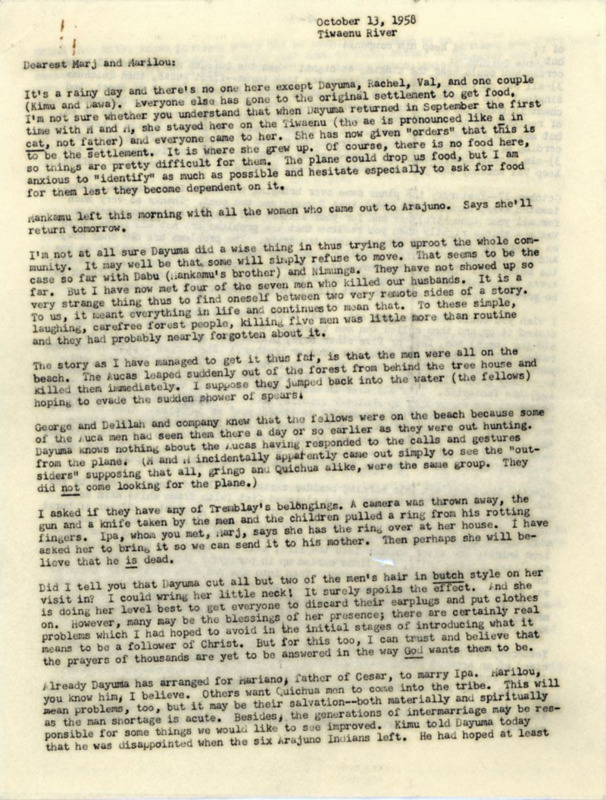

The mission to the Waorani took an unexpected turn a month later when two Waorani women emerged from the Amazon and met Elisabeth Elliot, who had been staying with the Tidmarshes in nearby Arajuno. Unable to communicate with the visitors, Elliot recorded their conversation and shipped the audio tapes to Rachel Saint and Dayuma, who were traveling in the United States on a speaking tour. Dayuma identified the women on the recording as her aunts Mankumu and Mintaka, seeking for news about their missing niece. After Dayuma and Rachel Saint returned to Ecuador in June 1958, Elisabeth Elliot facilitated a meeting of all three Waorani women at the SIL base in Limoncocha. After years of separation, Dayuma was reunited with her aunts and the three women returned to their Waorani kin. A few weeks later, Dayuma reappeared at the clearing near Arajuno with the announcement Elisabeth and Rachel had been waiting and praying for—an invitation to join the Waorani at their village in the rainforest.

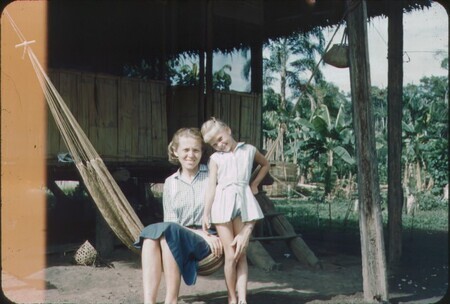

Over the next three years, Elisabeth and Rachel, along with three-year-old Valerie Elliot, lived intermittently with the Waorani group in a new settlement called Tewæno, constructing a rudimentary Wao language vocabulary and grammar. Through Bible stories translated into Wao by Dayuma, the two women also shared the gospel message of forgiveness and salvation.

Two decades later, Geuquita, the oldest member of the kin group and one of the attackers at Palm Beach, recounted how the arrival of Christianity impacted Waorani cycles of violence:

Before the kowode [outsiders] came and taught us about God we lived spearing. Back and forth, back and forth we speared, they died. We tried to stop killing. We would say “that's enough, leave off spearing.” Then someone would kill and we would return to killing back and forth. After hearing and believing in God, Kemo and I told them not to spear on our behalf, no matter how we died. And we ceased killing others back and forth. Just a few years ago when some young Waorani men killed my sister, I refused to spear on her behalf. Had I not believed, they would all be dead now.

Although their efforts marked the first sustained, peaceful contact with the Waorani people by outsiders, Rachel and Elisabeth’s strong personalities and disagreements over best methods for cross-cultural evangelism led to persistent conflicts. Elisabeth quietly left Tewæno with Valerie in 1961 and eventually returned to the United States. Rachel Saint remained with the Waorani people for the rest of her life.

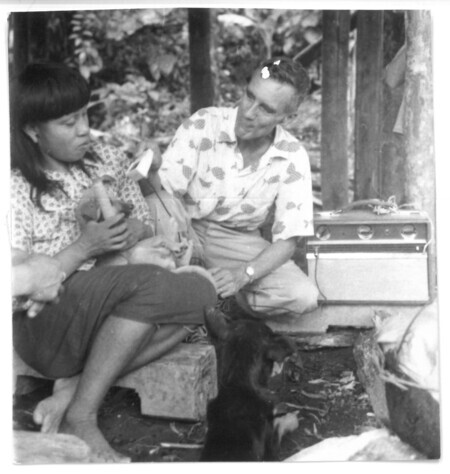

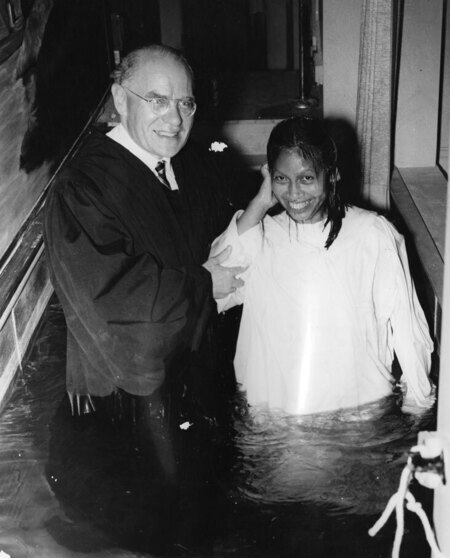

Throughout the 1960s, reports from Tewæno emphasized the growth of a new Waorani Christian community. In 1961, several Waorani men confessed faith in Christ, including Yowe, one of the five spearmen at Palm Beach. The new converts were baptized by Dr. Everett Fuller, a physician with HCJB. After years of meticulous labor, the Wao translation of the Gospel of Mark was dedicated in June 1965, followed a few months later by a Bible Conference in Tewæno hosted by former missionary and Wheaton College President, V. Raymond Edman. The following year, Quemo and Dayuma’s husband Come addressed hundreds of Christian leaders at the World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin, Germany, presenting the mission to the Waorani as a resounding success story for cross-cultural evangelism. Echoing the enthusiastic accounts of Rachel Saint and Elisabeth Elliot’s first entry into Waorani territory in 1958, evangelical press coverage reported widely on each development as testimonies to the transformative power of Christian grace and forgiveness.

This compelling narrative of sacrifice and redemption, however, often obscured difficult questions about the complex realities of cross-cultural missions, indigenous identity and autonomy amid Ecuador’s evolving economic interests. Although the conversion of the Waorani significantly reduced intergroup violence, the growing Waorani communities at Tewæno and elsewhere encountered new challenges from their contact with the world outside the rainforest—food scarcity, land rights disputes, forced relocations, contact diseases, and the slow creep of cultural assimilation. In the decades after Palm Beach, the Waorani questioned how to retain their distinct cultural identity while also adopting literacy and western habits. After abandoning their historic hostility toward outsiders, the once-isolated people group now struggled to navigate tensions between U.S. missionaries and the Ecuadorian government, incursions from anthropologists, and increasing pressure from oil and mining companies encroaching on indigenous lands.

Despite these significant challenges, the Waorani Christian community in Ecuador continued to grow—slowly gaining converts and developing indigenous church leaders, including members of the raiding party on Palm Beach. For many Waorani in the small community at Tewæno, the Christian message introduced and modeled by Dayuma, Rachel Saint, Elisabeth Elliot, and others, brought an end to the cyclical revenge killings and culture of violence that had plagued the kinship group and terrorized outsiders for decades. Others, like Catherine Peeke, devoted years to the slow and painstaking work of translating the Bible into the unwritten Wao language. The Wao tededo New Testament was dedicated in June 1992.

Today, seventy years after the tragic raid on Palm Beach, the story of “Operation Auca” and its ripple effects is still being retold through books, films, sermons, podcasts, exhibits, and personal narratives—continuing to fascinate audiences around the world with its powerful depiction of self-sacrifice, forgiveness, redemption. This exhibit tells only a partial story about the birth of the Waorani church and the five men—Jim Elliot, Peter Fleming, Ed McCully, Nate Saint, and Roger Youderian—and their families who gave the ultimate sacrifice to carry the light further.

Itota beyas, tsenonamai [On behalf of Jesus, do not spear].

![click to see item Black and white photograph of Waorani gathered in thatched structure. The reverse of the photograph includes two lengthy captions. The fist typed caption reads: "The Auca Church designed and built by themselves with a palm-thatched roof and bamboo floor. Here Dr. Edman held the first Bible Conference for these new Christians, and for the first time they celebrated the Lord's Supper. For bread they used boiled yuca (manioc or arrowroot) and for the wine they used banana drink in a gourd brought from the forest." The second handwritten caption reads: "Church designed and built by the Aucas, Tiwaeno. Bible class taught here Nov 4-5, 1965 by VRE. Mark 4 - Parable of the Sower (+ recd [?] from Ball Seed Co.). [?] meeting, Thurs. 11/4, by moonlight. Friday, 11/5, [?] on Baptism, Mark 16. 11 baptized, beginning with Dabo, and then Kimo and Dyuwi. Then the Lord's supper - first time for the Aucas - Mark 14 + 1 Cor 11, boiled [?] and banana drink. New song led by Dyuwi. The commissioning of Dyuwi and Tonia - Read Acts 13 - laying on of hand w/ Geo. M. Traber[?], Kimo, and VRE. Church lies between Rachel's and Dayuma's (background). Aucas planned church is for expansion when their [?] come to the Lord. Sept. '65."](/to-carry-the-light-further/objects/small/ca_b8740_sm.jpg)